The Australian Thoroughbred foal crop for 2023 is expected to decrease by 2 per cent, raising concerns about the impact on racing. However, while there may be fewer foals, data suggests race fields and wagering aren’t suffering, with stable field sizes and a record number of individual runners in the 2022/23 season. The real challenge lies not in the number of horses available, but in finding enough owners to sustain the industry.

In the opening article in this series it was established that the Australian Thoroughbred foal crop for the 2023 foaling season is expected to finish down 2 per cent at around 12,800. Amongst the first concerns with a diminishing foal crop is will there be enough horses to sustain the amount of racing that we have? I contend stock for racing won’t be an issue, finding owners for them more problematic.

Read: Foal crop review: What should we expect this spring?

Racing numbers hold steady

The figures published in the Racing Australia Fact Book for the 2022/23 season suggest that, despite a continual decline in foals born, it isn’t having an effect on race fields and therefore shouldn’t be linked to the current downturn in betting turnover. In terms of race meeting numbers one less washout and the total number of fixtures would have tallied 2600 for the first time since the 2018/19 season, and the 19,462 races run across the country was the highest for nine years.

| Year | Total Races | Total Starters |

|---|---|---|

| 2022/23 | 19,462 | 183,304 |

| 2021/22 | 18,917 | 177,354 |

| 2020/21 | 19,026 | 179,270 |

| 2019/20 | 18,535 | 178,640 |

| 2018/19 | 19,369 | 181,981 |

| 2017/18 | 19,409 | 180,933 |

| 2016/17 | 19,235 | 182,868 |

| 2015/16 | 19,393 | 186,141 |

| 2014/15 | 18,949 | 184,800 |

| 2013/14 | 19,511 | 189,259 |

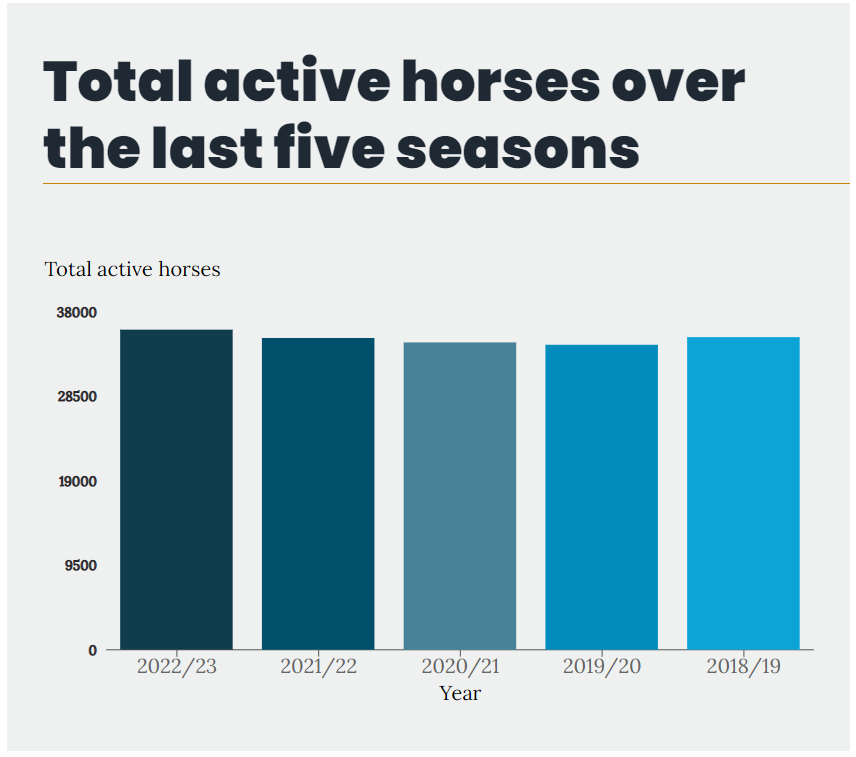

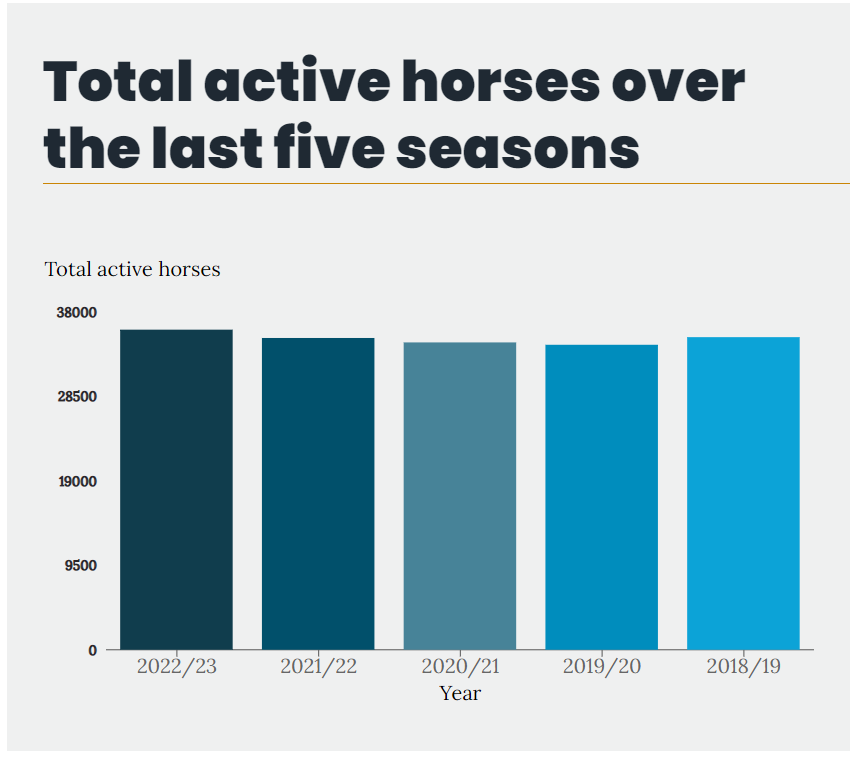

And it is not like field sizes are declining. The peak for the last decade came in 2015/16 at a national average of 9.71 starters per race. While the numbers fell in the years straight after, the figure has plateaued at 9.4 per race for the five seasons to 2022/23. Everyone would like that to be higher, but whatever ills the wagering sector may have caught, they haven’t come from fewer horses to gamble on. And just to emphasise a point, for the first time in seven years the number of individual runners broke 36,000 in 22/23, a rise of 3.3 per cent on the previous season.

Of course, these were horses purchased in the good ol’ days of COVID when the market, particularly the yearling sector, was awash with disposable income that couldn’t be spent on overseas holidays etc,. That is reflected in the number of individual owners within the industry which climbed 71 per cent in five years to peak at 141,190, although the 22/23 season saw a significant slowdown in growth which tallies with difficulties the syndication market faces. True, there are thunder clouds gathering but in the 150 years or so the Australian Thoroughbred industry has been a truly commercial enterprise, the industry has ridden out worse storms before.

The rising European influence

So, with foal numbers down the market must be being propped up by imports, right? The answer, to a degree, is yes as the number of GB, Ire and Fr suffixes in our form guides, particularly the latter, continue to rise. And why not? On top of the purchase price of buying a yearling unlikely to feature in our Group 1 juvenile races, any horse could cost the ownership group, depending on maturity and where the trainer is based, the best part of $80,000 to $100,000 before they are urged to put their precious gelding online. In the imported tried-horse market the biggest trap is acclimatisation, but if the neddy can put one foot in front of the other then the chances of getting a return, particularly in the middle-distance and staying race categories where the ratio of prizemoney versus serious opposition gives an owner an edge, are enhanced greatly.

And as the gap between prizemoney in Australia and the major European jurisdictions continues to widen, so does the buying power between the various countries. Only the very unlikely return to 1980s exchange rates when an Aussie dollar could only buy you forty pence might our advantage disappear. While that is far-fetched, if the new Labor government in Britain under Sir Kheir Starmer can turn water into wine and fix its basket-case of an economy we might at least see a shift of a couple of cents in the coming few years.

| Year | Total Imports | Total Exports |

|---|---|---|

| 2022/23 | 2572 | 1262 |

| 2021/22 | 3038 | 1186 |

| 2020/21 | 3031 | 1263 |

| 2019/20 | 2489 | 1274 |

| 2018/19 | 2686 | 1662 |

| 2017/18 | 2726 | 1756 |

| 2016/17 | 2591 | 1686 |

| 2015/16 | 1789 | 1739 |

Interestingly, a renewed faith in the local market in New Zealand triggered a 400-plus fall in the number of Kiwi imports, although it is fair to say most of those would only be 2-year-olds now. And it’s not as if the bottom has fallen out of the export market, although while new opportunities in Asia will come through, the 242 horses previously earmarked for Singapore and Macau will need to be replaced. The saviour might be the Hong Kong Jockey Club, the recent announcement by their CEO Winfried Engelbrecht-Bresges that they need to increase field sizes led to a spike in the number of Australian trainers taking calls starting with an +852 area code.

Three major factors

So, if it’s not any of the above just how has the industry survived? I think there are three major factors shaping the racing landscape in the 2020’s.

Firstly, the obvious, levels of prizemoney that border on incredulous. If you put aside the initial outlay for the horse, then for the majority of owners it is very much about the beast paying as many of the training bills as their ability will allow. Not that long ago a provincial or country trained horse needed to win an unlikely three or more races a season to cover operating expenses, but now in New South Wales that is much closer to two victories despite increases in daily rates.

Inflated prizemoney has also changed the landscape at the elite end of the sport where we are witnessing a lot more mares racing into their six and 7-year-old seasons for purely economic reasons. If a quality mare can retain her zest for racing and turn of foot then there are enough seven-figure prizemoney races around that success in just one, and in some cases even a silver medal, is enough to outstrip what the market might potentially pay for her first foal. The commercial nature of stallions means they’ll still be packed off to stud as the human equivalent of a teenager, but for mares one more season could be quite lucrative.

Also, those Fact Book figures show that over the past four seasons there were 1000 more horses racing with significant growth in the number of five-, six- and 7-year-olds still strutting their stuff. Of course, your average owner in a country town isn’t thinking of another crack at the Queen Elizabeth or a Quokka, but anecdotally, there isn’t the rush to find a home for horses with wallet-draining moderate ability as there was, say, 10 years ago.

The third development goes hand in hoof with the longevity of the horse, and that’s advances in veterinary science. This is also somewhat word of mouth sprinkled with a dash of personal experience, but by way of example the number of horses successfully treated for wind infirmities and tendon issues must be on the rise. As an example, horses can ‘go in the wind’ as often as they once did but through the wonders of science, and the lure of solid prizemoney to pay for the operation, owners are more willing to keep the horse racing, particularly mares for whom black type might have been just a stride or two away.

Ancillary services remain resilient

Of course, our industry isn’t just about the owner, breeder and trainer. As I understand things for the moment those offering ancillary services to the industry such as farriers, feed merchants and agistment farms haven’t been affected while the number of horses in training remains buoyant. However, they are under pressure to maintain charges at their current level, or even offer a discount, while general inflation is driving up business costs around them.

One small bonus with a declining foal crop is our reliance on aftercare and rehoming programs would diminish in line. The figures here get very hazy depending on just how many make it to the point they can be rehomed, but based on registration data and guesstimating how many geldings might be retired we would be looking at roughly 100 less horses per year and add another 20-30 mares not considered commercially viable breeding stock.

So, there is every indication that a small drop in foals born is sustainable for the present time, but the question has to be asked if we still have an ownership base broad enough to maintain the requisite number of horses in training. I’ll delve into that in the final article.

This article was written by Glen Latham for TTRAusNZ.